Carlisle Co. (CSL-US) - A hidden gem in plain sight

This conglomerate is breaking up; its core asset is both high-quality, significantly undervalued and I believe misunderstood. I see clear catalysts for value-unlock over 3-5 years.

Share Price: $224.32

Market Cap: $11.4bn

Debt: $2.2bn

EV: $13.6bn

2023e EPS: $21.20

2023e P/E: 10.6x

2023e EBITDA: $1,559

2023e EV/EBITDA: 8.7x

Introduction

Carlisle Companies is one of the more interesting investment oppourtunities I’ve come across in a while. I think it is both cheap, high-quality, misunderstood and has clear catalysts for re-rating to a more sensible valuation. The 3-5 year risk/reward is very attractive.

I’m not going to give a description of what the business “does”, so maybe read the 10-k first. But it’s a pretty simple business.

Transperancy statement: I started buying this at $258 and I’ve been buying down with all this bankrun overhang. My average is $247. I have a pretty big chunk of my net worth in this stock now and will probably buy more. This isn’t financial advice - do your own research.

Wanna chat Carlisle? Email me: guastywinds@gmail.com. I might share my model if you ask nice enough.

High-level overview in 5 key points

Carlisle’s roofing business, which comprises the majority of its construction materials earnings, is high-quality and under-appreciated. It is a leader in an oligopolistic market structure, has defensive qualities due to high (~65-70%) exposure to non-discretionary re-roofing, is capital light and has a mostly variable cost-structure (allowing it to still generate significant cashflows through the GFC). Carlisle should grow due to (1) growing re-roof demand from buildings completed in the late 90s and early 00s that now need replacing (average age of roof = 20-25 years), (2) energy efficiency trends increasing content in the building envelope, such as spray-foam, polyiso and air-barriers. Management is confident that the business can grown ~MSD through to the end of the decade.

Carlisle is an old conglomerate that has undergone significant simplification over recent years. The company is still being valued like an old conglomerate, and the value of the underlying roofing business is not well appreciated. This is partly because the stock is not well followed - it has no major brokers, despite having a $11.5bn capitalization - and because the simplification is not yet complete (there still remains two non-related businesses which make up ~20% of sales, which are by all accounts for sale). Currently, Carlisle trades at ~10.5x consensus P/E for 2023e. I think it is worth closer to 16-20x - similar to something like Rockwool or Kingspan. In addition, two peer transactions were recently done (Firestone in 2021 and DuroLast in early 2023) at ~12x EBITDA - today, Carlisle (the clear industry leader) trades at 8.7x. I see that as a significant disclocation.

Beyond the conglomerate discount, two other cyclical concerns are weighing on the valuation. There are two points to address:

Volumes: Whilst volumes have been strong in 2022/2021, 2020 was down ~8% and capacity/labour constraints put a dampener on the industry’s ability to respond. Hence, volumes from 2019-2022 only grew at ~4%, versus the company’s pre-covid expectations for MSD. Given that a signficant portion of revenues are re-roof, which is largely non-discretionary in nature, revenue is resilient over-time. My channel checks (including two largest contractors and distributors in the nation) suggest that backlogs remain healthy and there is still a large amount of re-roof activity which has been deferred and constrained through covid. Whilst a slowdown in volumes is inevitable at some point (I model 2024e -4%), I think that concerns for a significant drop in volumes are probably overstated. Sales in this business have only ever declined in one-year since 1991, and that was 2008, from which they promptly recovered within two years. The largely non-discretionary nature of the business gives it natural resiliency over the medium-term.

Pricing: Pricing has surged throughout Covid and is likely up in the region of ~40% since 2019, and as a result, Carlisle has expanded its EBITDA margins from ~23% to ~31%. The market is concerned that the increased profitability in the segment is temporary, however under-the-hood, there have been structural changes. These include (1) ownership changes of major players, (2) management personnel changes at a key competitor, and (3) shifting mindset in the industry as a ‘volume-growth’ business to one that is more value-oriented. I also find that whilst prices have risen, they have predominately done so in the TPO product, which was (and still remains) the cheapest roofing membrane material (I will go into this in detail below). TPO membranes on my estimates comprise maybe ~5-10% of the total roof job, and hence I think pricing power is underappreciated. My view is that margins are more sustainable than the market is giving the company credit for. In addition, the company should benefit from materials deflation this year (mostly oil-linked resins/polymers) which will provide support to margins even if pricing slips a bit.

Since the management change in ~2015, the company has a good capital allocation track-record. It has begun paying a dividend, repurchasing stock and exiting business. The share-count has shrunk by over 20% since 2015. The cpy. has also done a few acquisition at post-synnergies multiples of 7-10.5x EBITDA. I expect that the company will continue to repurchase stock whilst its share price remains so cheap.

There are two catalysts to re-rating. First, the company needs to sell off its two other remaining businesses. This might take a bit of time, but it will inevitably come and cash will likely be used to repurchase stock or do accretive acquisitions. Second, the company needs to show that current margins are more sustainable. This might take a few quarters or even a year-or-two to prove out.

I think Carlisle has a clear path to do ~$29 of EPS in 2027e even with a partial retracement in margins and softness in volumes in 2024 (I walk through my assumptions at the end). I think a 16x P/E multiple is sensible with room for upside. Pick your multiple - it’s still cheap at 14x P/E. I’m just sure it is worth more than 10.5x P/E. My price target is hence $462 (current price, $223) and I think a 4-year IRR including dividends of ~20%+ is achievable, even when assuming negative volumes and margin compression in 2024.

My upside case gives IRR of 27% and if we assume margins contract back to 2019 levels and 14x P/E, we still get 11% IRR. I think it is a very attractive risk/reward.

Risks/Where would I be wrong

Obviously, Macro and all that. If you think the world is ending then maybe don’t buy the stock, or stocks at all. I think that roofing will slow in coming years and I’ve built that into my model but I don’t think the world is ending. The nice thing about the non-discretionary nature of re-roofs, which drives a big chunk of the business, is that revenues lost today are revenues gained tomorrow. Interest rates don’t generally effect how much it hails (I haven’t actually looked at the correlation). Don’t get me wrong - there is still newbuild and some resi - the business is cyclical. But it’s not as cyclical/discretionary as you might intuitively think.

Margins. If I’m wrong I think it’s probably because I got margins wrong. I think this is a rational industry which has become more so. Could one of these guys get really aggresive and start pushing product into the market really cheaply? It’s possible if we have a GFC-esque event. I chat about this in detail below. It’s the biggest LT risk, and whilst I have built in ~3.5 points of margin compression in 2024, if we sit here with 22% margins, 2027e EPS will be, understandably, a bit lower. That said, as I illustrate at the end, even with 22% terminal margins and a 14x P/E multiple, our IRR is ~11%.

Asset sales/general capital allocation. The company needs to sell these non-core assets to re-rate. If we’re stuck holding them, or forced to sell at a really cheap price, then it will take longer to re-rate. I have no insight into this. The company has sold multiple large assets in the past decade so I’m sure they’ll get it done. I’m similarly not holding my breath on both getting done in 2023. My assumptions on sales prices are (I think) sufficiently conservative. Mgmt. could also blow us up with a big expensive asset purchase, but their track-record is pretty solid.

Why is the market giving us this oppourtunity?

These, I think, are the key reasons.

General cyclical conerns.

Conglomerate discount and messy past financials (at group level, underlying biz is clean).

Not much coverage (no buldge-bracket banks, Jefferies is the biggest broker).

Under-appreciation for the structural changes that will likely lead to higher go-forward margins. Market thinks they are not sustainable.

Under-appreciation for the structural growth drivers of the business.

Contents and key points of my thesis

Brief history of Carlisle and the roofing industry.

Quick Roofing Industry Overview - fundemantals of commercial roofing.

Why Roofing is a nice business, and how the industry has structurally changed.

Structural Growth - Go Green or Go Home.

Numbers - Valuation and Forecasts.

Brief History of Carlisle

Carlisle is a 100+ year old industrial conglomerate, whose business was originally rubber manufacturing. In the post-war era, Carlisle followed its peers into ‘multi-industry’ and underwent significant diversification. It was George Ohrstrom who steered them this way (industrial history nerds will know him as the guy who built Dover and Roper). Come the turn of the century, Carlisle was involved in a plethora of commodity manufacturing businesses - all-in, a pretty unremarkable conglomerate. However, standing at ~20% of sales in 2000, was a hidden gem - Carlise Syntec.

In the early 1960s, some chemical engineers at Carlisle were experimenting with a material called Butyl for waterproofing farmers haystacks and from that they developed a new type of material called EPDM. It has both excellent waterproofing abilities and ozone resistance. One brilliant engineer decided that perhaps EPDM could make a great material for roofs, and thus in 1962 the synthetic roofing industry was born.

Prior to this, the way to build a commercial flat roof was asphalt ‘built-up-roofing (BUR)’, where they would lug a hot kettle of asphalt onto the roof and mop it on with layers of fiberglass as membranes. It was expensive, labour-intensive, and bloody hard work! Watch this video below.

Synthetic roofing started to gain a little bit of traction in the 60s due to its lower cost and labour intensity, but it was in the 1970s when the oil embargo caused issues with the price and availability of asphalt that synthetic roofing really took off. The industry scrambled for alternatives, and the synthetic roofing industry gained serious acceptance. Through the 70s and 80s it boomed, and it attracted the interest of many players - both large rubber manufacturers and new entrants.

By the mid 1980s, despite its strong growth, synthetic roofing was largely a profitless wasteland. Firestone, who had once come to dominate the tire business by using excessive scale to price competitors out, employed the same strategy in roofing and managed to gain a strong foothold in the industry. I even heard an anecdote that they used to give away a free flat-bed truck with every 20 roofs (or something like that).

However, it turned out that manufacturing this stuff well and cheaply was actually a pretty tough thing to do. Lots of companies had quality issues, and by necesity, the industry consolidated. By the early 1990s, the many of the smaller companies either went broke or were gobbled up by Firestone or Carlisle. The big four rubber manufacturers, due to their scale and expertise working with the matieral, came to dominate the industry. And then by the early 90s, it become two - Goodyear sold their business to Carlisle and General Rubber sold theirs to Firestone. Even today, EPDM is largely a two-player duopoly, with a small amount of share from Johns Manville. Anyone else who claims to be selling EPDM is just white-labelling one of these three manufacturers.

Even in the early 90s, it was by all accounts a really nice business. In 1991, Carlisle Syntec did $28m of EBITDA on a sales base of ~$200m and on a total asset base of $102m, a cool 27% return on assets. It only spent ~$3m in capital. What a business!

However, whilst EPDM would continue to boom through to the early 2000s, two new materials would come to rival its success. First was PVC - a plastic material that was popular in Europe, and the latter was TPO. PVC had some early success, but ran into quality problems as the original manufactures didn’t tailor the product enough for the US climate. PVC had some benefits over EPDM - namely, it was white, which meant that it reflected heat instead of absorbed (EPDM is black and hence absorbs heat - not good for south-western climates). However, PVC never really took off in the US in the same way that it did in Europe, partially due to (1) cost - its an expensive material and much was being imported, (2) early reputational issues and (3) the rise of TPO.

Carlisle first commercialised TPO in 1998, which was a science project at Versico (Goodyear) when they bought that business in 1993. TPO was a huge success - it was white and significantly cheaper than PVC with similar benefits. Whilst it wasn’t yet cheaper than EPDM, the industry knew that with scale, it could make it so. TPO had some early issues too, as any new material does, but over time TPO proved itself as a good material and it helped accelerate the synthetic market’s rise against asphalt.

The introduction of TPO, of course, attracted new entrants. Synthetic was taking share from asphalt really quickly through the 90s (Carlisle grew from $200m in 1991 to $400m in 1999). The asphalt guys, namely GAF and Johns Manville, saw TPO as an oppourunity to get into the market of synthetic roofing, and they took that. Firestone couldn’t get their TPO right organically, and bought a leading new entrant, but they caught up eventually.

For those unaware, GAF and JM are two of the largest roofing manufacturers across the US, across both residential and commercial. The channel (distribution and contract work) for resi and commercial has a lot of synergy, so it made sense for these guys to try play here and try save their commercial asphalt businesses from shrinking. No non-roofing players managed to get a foothold, and it’s really hard to do organically. I’ll go through that in more detail later. Others came in, but either got bought or failed. Today, TPO is mostly a 4 player market, with much of the share split between Firestone and Carlisle.

At the turn of the century, asphalt comprised still >50% of the roofing industry. TPO was just being introduced and it grew like wildfire, taking signficant amounts of share from asphalt through the early 00s. As TPO got scale throughout the early 00s, it managed to get priced much lower than PVC and even lower than the more mature EPDM, which helped it grow to become what is today by-far the most popular membrane.

Over time, the company also did a few smart acquistions in the polyiso space and grew it organically. Over time, that market consolidated signficiantly such that most of the polyiso insulation market is now owned by the commercial roofing manufacturers. Most roofs are sold as total systems with “system warranties” and insulation can’t be changed without changing the roof, so that level of vertical integration makes a lot of sense.

Below is an illustration of three-decades of success for Carlisle’s roofing business - most of which was organic (up until last few years - I give more in-depth breakdown later). Also pay attention to how the company performed through 2000 and during the GFC - profitability was really solid. Note: there was a shuffling in segments in 2020 - sales were down 7.5% organically, it looks much worse on the chart.

Despite huge successes in the roofing business, Carlisle as a whole was still largely comprised of other commodity manufacturing businesses come 2008. These were exposed to highly cyclical and competitive industries such as automotive (brakes and tires), heavy machinery and vehicles, trucks, industrial components, power transmission as well as legacy rubber manufacturing. The businesses all suffered pretty bad from the GFC, and the company was forced to re-structure both organically and inorganically. Despite incredible growth, in 2007, Roofing was still less than 50% of sales.

In 2009, the company kickstarted a simplification strategy. The first leg was simply getting out of businesses which had been permanently hampered by the GFC. The trucks/trailer business was losing money, for example, and few other businesses were left in such a state of overcapacity that they weren’t hitting their returns on capital.

The company would go on to sell a couple of businesses, though the second wave of simplification would really come in 2013 when Christian Koch took over as CEO. Koch accelerated the simplification strategy, and steered the business towards “high-value industries” - that being, CIT (interconnects - think similar to Ametek), CFT (Fluid control - think similar to Graco) and CCM (Construction Materials - mostly roofing/polyiso). He also began to repurchase stock and pay a dividend at this point.

This was a pretty succesful strategy and got the company’s portfolio to the position that it is in today. Below is a high-level overview of the path taken. The stock performed quite well over this period.

After Covid, the company changed it’s tone a further time to pivot entirely towards building materials. CFT and CIT, the other two assets, would be sold, and the company would become a pure-play specialty construction materials company focussed on the ‘building envelope’. Whilst a vast majority of the simplifaction is complete, Carlisle still has two businesses (CIT and CFT) which are comprising ~17% of sales.

Quick Roofing Industry Overview - Fundemantals of Commercial Roofing

I’m going to keep this brief-ish because there is a lot of information out there on commercial roofing and you guys can go read for yourself. Below should give you a good primer.

On Products

Here is a great resource on the different membranes which I took from some website. I couldn’t find the source so if this is your website, sorry!

Here is a really good lecture from a Firestone rep. It’s a bit old but pretty good:

Here is a good video on how TPO and EPDM are installed (gives you a sense for the products and the sense that this is a true ‘system’).

I’d say it’s good to watch the first video so you can follow along, but it isn’t abolsutely required. The installation videos are more just for the nerds out there that like to understand the products and how they work, but again, it’s not neccesity.

Market Structure

The three major synethetic materials are TPO, EPDM and PVC. Estimates I have seen suggest that TPO is ~50-60% of the market, EPDM is 15-20% and PVC is ~10-15%, then asphalt is somewhere in the 5-10% range. This isn’t exact and there are big geographical differences, and I get different numbers from different channel checks, but it’s a good proxy.

TPO is manufactured by Carlisle, Firestone, GAF and Johns Manville. TKO, a canadian manfuacturer, also have a small plant. Market shares are available but I estimate that Carlisle and Firestone probably have ~30-35% each, GAF has maybe 15-20%, JM and TKO probably have 5-10%.

EPDM is manufactured by Firestone, Carlise and JM. Estimates I have seen suggest that Firestone and Carlisle probably have 40-45% market share each, and the remainder sits with JM.

PVC is manufactured by everyone other than JM (I think). Carlisle only has a small exposure to PVC, and my understanding is that they only play in high-end product. There are two big private players - Durolast (who just got bought by Firestone) and IB Roof Systems. Sika also has a PVC business.

There are a bunch of players in Asphalt, but GAF and Johns Manville are big players there. Carlisle doesn’t touch asphalt.

So the four major players are: Carlisle, Firestone, GAF and Johns Manville.

Is this a good business?

Those that know me know that I have a building products fetish. Carlisle ticks pretty much all of the boxes for what makes a good building products company.

I have a very simple mental framework for building products that I think works ~90% of the time. It’s maybe a bit too simple, but it works for me as a good starting point. It’s two questions:

Is the industry consolidated or fragmented?

Is the cost-base variable or fixed?

It sounds pretty obvious, but it works. Consolidated and variable cost is important because this is a cyclical and seasonal industry. If you are a fixed-cost biz, there will naturally be a lot of price competition. And fragmented industries just usually aren’t good for anyone. But being consolidated isn’t good enough. Insulation (fiberglass bats) is a great example. There are only 4 players, but it’s brutally competetive and the returns on capital over the last decade have been pretty average. OSB is the same - swings in price and profits are huge.

Shingles, paint, plumbing fixtures, commercial ceiling tiles, HVAC systems (both residential and commercial), electrical systems (both residenital and commercial), composite decking - all variable cost and all consolidated 3-4 player markets. All high return on capital businesses.

If you’re in a fragmented and/or fixed cost business, you’re probably not making much money. Windows, cabinets, flooring and some specific low-end siding is like this.

Carlisle is both consolidated and variable cost, so that’s a nice starting point.

Barriers - Not impossible but pretty high

One of the underappreciated niceties of the building products industry is that the supply chain is hard to crack - really hard. Go have a look at your house and tell me how many Chinese manufactured products there are. I bet you won’t find many. And then tell me how many products were manufactured by companies that were founded in the last 30 years. Probably zilch if not very few. It’s not because Chinese products aren’t good, and it’s not because they aren’t cheaper.

There are three key barriers in building products. The first is getting accepted by contractors who install the product. The second is getting the distributors to hold your product. The third is getting all the other parties on-board - those being the engineers, the roofing consultants, the architects.

Typically a roofing project will look something like this:

Owner has a roofing project, either new-build or re-roof.

If new-build, they hire an architect who hires a general contractor, and they will hire roof consultants/engineers (or may have so in-house, if large enough) to design the technical specs of a roof. That spec will then be written, and a vendor will be written into the spec (generally a preferred vendor of the architect). For a re-roof, it looks similar, but there is not a GC/architect involved, it usually goes straight to a consultant or a subcontractor who will involve engineers/consultants.

Then the GC hires a subcontractor. The subbie is given the specs. They work with their local distributor to procure what they need. They will also work with a manfacturers rep (a sales person for the roof vendor) who can help them find the exact products that they need for the job. Then the subbie procures and installs the roof.

The key issues are such:

The key decision-markers are the architects and consultants, but they are hard to sway because they’ve been working with Carlisle/Firestone for decades and had lots of success. They also are not motivated by saving a few bucks here or there. In-fact, often they are incentivised on a % of project cost, so they don’t really care if you’re gonna come in 5-10% lower on a particularly product.

Architects and Engineers reputations are based on the efficacy of their work. If they spec in a product that nobody has heard of and it goes bad, it reflects poorly on them. It is double-bad (for them and for the subcontractor) if that particular vendor goes out of business and isn’t around in 20 years when they need a warranty claim. Carlisle and Firestone aren’t going out of business any time soon. Chinese Roof Company LTD who’s barely sold any product might not be around in 20 years. That’s not a chance worth taking.

For the subbies - this stuff is complex. Every roof project is engineered and specified - no two roofs are the same. So you need to get properly trained and certified on a particular company’s products. That is a time-consuming and expensive task. Getting your whole crew certified on a new product is expensive and time-consuming. Also, you’re probably gonna be less efficient at installing the new product than you would be with Carlisle’s system, which they’ve been installing you 30 years. Roofing labour is perhaps some of the tightest in the country and it’s getting worse every year. They don’t have spare time to spend getting certified on products that they won’t install.

Most distributors are on exclusive relationships. I.e. Carlisle tells SRS in California that we’ll only let you and maybe one other distributor in the state sell our product - that means every subbie that gets written a spec for Carlisle (lots of them) has to come to you/a select few to get product. In return, you can’t carry competitors products (or it might be that you can only carry us and Firestone, or us and GAF, or something like that - it’ll depend on region, the distributors market share in that region and the vendors’ market share in that region). Generally, the top vendors are split between the top distributors in any particular region. Breaking into that is tough. And why are you, as a distributor, going to risk your business (and working capital) on an unproven membrane from an unproven vendor. You probably aren’t.

So, the architects and consultants have no incentive to spec in cheap product. The subbies aren’t trained or familiar with this new product, so there is no incentive for them to try influence the spec and risk their reputation on an unproven new product with no track-record (and take the warranty risk). And if they aren’t getting the product written in spec, then they aren’t incentivised to go out and get the training. So, the distributor won’t hold the product if it isn’t being specc’d, and then if the distributor isn’t holding the product, there is even less incentive for the subbie the get trained on/flip-the-spec on a new product because it isn’t easily available anyway.

No one of these things in and of themselves makes it impossible for entrants to come in, but when you put it all together, it’s very difficult to take share. It’s a classic chicken and egg problem. Not to mention that actually making this stuff is hard if you have no knowledge of the roofing business. And building a plant can take 3-5 years - it’s a huge capital investment. The roof contractor business is local and fragmented - the biggest player has 15%. Certifying all the roofers across the country will take many years, likely decades.

Now, yes, there have been a few entrants into the industry since Carlisle and Firestone - those are GAF, JM and a small plant in 2021 from IKO. What do these all have in common? They are all roofing manufacturers that have pre-existing relationships/trust with subbies, distributors and architects/engineers for commercial asphalt. And even then, it took them a while to get a foothold.

So could IKO be a little bigger in 5-10 years? Sure. What will the roofing industry look like in 10-20-30 years? Well, the membranes might be made of different materials and maybe market shares will go up or down a little, but I suspect it won’t look a whole lot different. You can’t say that about many other businesses.

Competition - Pretty rational, getting better

It is a consolidated industry. History of competition has been pretty rational, evidenced by the company’s smooth-ish margins through time. There have been bumps - in the 2013-16ish period, a fair bit of new capacity got added to the market after the industry returned to strong growth post-GFC which it needed to absorb, so pricing was soft. When I say soft, I mean down ~4%ish in total over 4 years.

This was also somewhat excacerbated by the fact that GAF and JM were tying hard to get a foothold in the market that Firestone and Carlisle had dominated for so long. And as I mentioned in the barriers section, it’s hard to get in. So, to get in, you need to use kickbacks and incentives to move product. For JM and GAF, it was less about absorbing fixed costs, and more about getting acceptance in the market.

What compounded this was the fact that JM and GAF both had declining asphalt businesses, so they had to be aggresive to get a foothold in the growing synthetics market before it matured and the asphalt business went to zero. Hence, GAF and JM have not always been totally rational. You can see in Carlisle’s margins that this has never been an overly competitive industry, but there have been periods of softer margins, particularly around capacity additions, where JM and GAF have forced softer pricing to move product. As you can see below, there was a soft pricing period. Note: The company no longer discloses pricing.

So, my read is that 5-10 years ago, this business was pretty rational but still competitve as it was growing fast and volumes was the name of the game. Today, some things have changed, which I adress next.

There are a couple of points I want to make here.

Management and ownership changes at the major manufacturers should be conducive for better price discipline.

Increasing ‘maturity’ of the industry is a structural positive for rational behaviour.

Industry economics support high-returns and rational behaviour.

Management and Ownership changes at the major manufacturers

In the early 2010s, Carlisle started talking about price discipline more, which started with walking away from a bunch of business in Canada. Though margins tend to fluctuate with raw materials, over-time, the company has increased margins leading up to Covid. This is a mixture of increased rationality in the industry and cost-discipline.

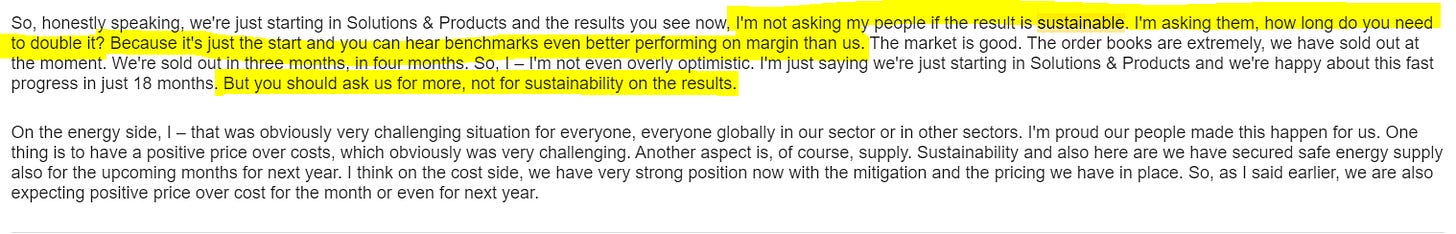

Carlisle has always been the leader in the industry; nothing has changed from that perspective. They are playing to hold price and margin - their position on the situation is clear (from 1Q22 earnings call below).

However, it’s never been Carlisle that was the problem - it was their competitors who put pressure on pricing, as discussed earlier. There are strong signs that this is changing also.

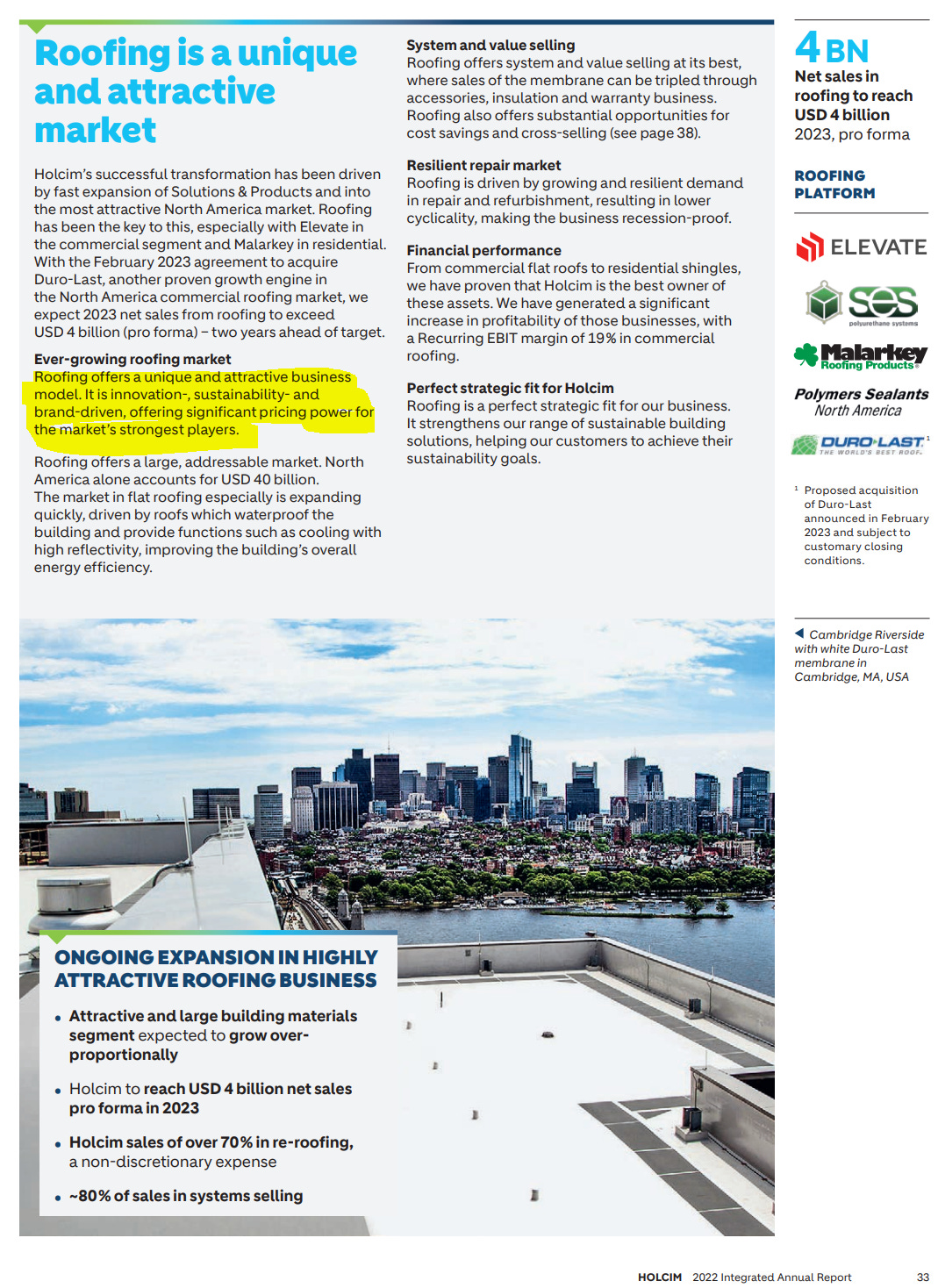

In 2021, Firestone (#2 in the industry) got bought by Holcim. Firestone was historically, according my checks, a more aggresive player in the industry. Already, we have seen discipline from Firestone in the marketplace, pushing price increases in-line with Carlisle and also raising prices on their ancillary system products to be more in-line with Carlisle. Whilst it’s too early to say how they will act in a downturn, we can look to Holcim’s earnings calls for a suggestion on how they might behave.

From 4Q22:

From 3Q22:

So Holcim’s position on margins is clear - they’ve put a bunch of capital to work on US Roofing (including a number of other acquisitions in Malarkey, DuroLast, Adhesives business from ITW and SES Foams to build out the portfolio) and they want to show a return on that. Carlisle has ~28% EBIT margins compared to Firestone at ~19% in roofing for 2022. Firestone wants to get to Carlisle level margins, and it won’t do so by cutting price.

Holcim has also made consistent comments about the ‘pricing power’ in the roofing business. From the 2022 annual report. They understand the business that they are in.

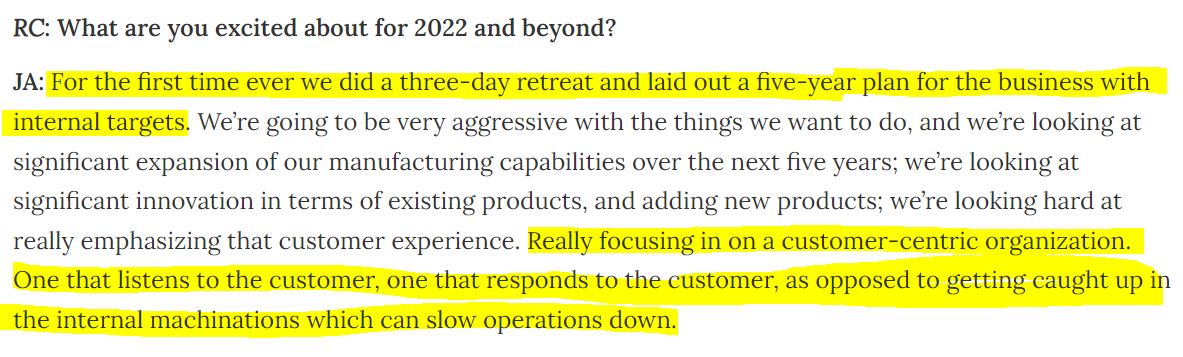

There has also been a big change at #3 player, GAF. From 1998-2018, Carlisle’s roofing business was run by a man named John Altmeyer. John is a legend in the roofing industry, and played a big part of pushing Carlisle towards the ‘system-sale’, focussing on value over price.

In early 2021, John was made chairman of GAF’s commercial roofing business. Then, in January 2023, he was made CEO of GAF commercial.

Many speculate that with GAF’s new leadership, it will be more rational. Here is a great Q&A with John from RoofingContractor Magazine, where John talks about his ambitions for GAF. Below is one important snippet.

John is going to re-invigorate GAF, and it will likely become a tougher competitor going forward. However, I view this as a signficant net-benefit for the industry. GAF, being focussed on customer service and product R&D with internal targets (presumably including profitability), instead of focussed on winning business by being the cheapest, it a positive development for everyone in the industry.

JM is a question-mark, and I really don’t have any insight into them. IKO similar, and they’ll probably be a bit more aggresive, but they are so small that it shouldn’t impact much. To have the big three all being publically vocal about price discipline is a good sign.

It’s too early to say how the industry is going to behave, because all of these changes have occured since 2021, and the industry has been in post-covid boom-mode since. A minor positive is that the 4Q22/1Q23 large channel destock that we’re seeing has not impacted pricing at all (confirmed via conversations with channel).

As a quick aside - and I realise that these sorts of anecdotes aren’t always helpful - but a similar thing did happen in the residential roofing industry. Through the 00s, the roofing industry consolidated considerably.

Over this period, Residential Roofing went from a low-margin (~5-10% EBIT pre-GFC) business, to one that now does 22% (according to OC filings in 2022). It has a lot of similarities with commercial in terms of drivers (high re-roof), channels and cost-base (oil-linked, variable cost). GAF also plays in both markets. It’s just an anecdote, but there’s precedent for building products industries that undergo consolidation and see higher margins as a result in the future.

So, my view is that changes at GAF and Firestone are structural and supportive of higher margins going forward.

Increasing ‘maturity’ of the industry

I already touched on this earlier, so I will be brief. The industry has become more mature. Capacity additions now add ~3% instead of 5-6% that they may have 10 years ago, and volume growth is far more modest now that the ‘asphalt tailwind’ has by-and-large come to an end. Hence, capacity additions going forward will both (1) have less of an impact on overall S/D (and be more managable), and (2) be more measured and modest.

When you have expectations for an industry growing at 7-8%, and especially when you need to grab volume to protect your shrinking asphalt business and establish yourself, you’ll naturally push harder on volumes to get a foothold in the industry. This also makes sense because more volumes can be absorbed via share-gains from asphalt.

Today, volume growth will be far more modest - it’s more a function of construction and re-roofs. I think this is driving the changing mindset of the manufacturers. It’s no longer a sexy high-growth industry. It’s a modest but predictable growth industry, which should bring forward more rational behaviour.

Industry economics are supportive of price discipline

I’ve already touched on this, so again, I will be brief. This is a mostly variable cost business - 85% of COGS are raws - and capital costs are only ~2-3% of sales, which is ~7-10% of EBITDA. This is not an industry which has significant fixed-costs to cover when volumes fall. It also has a natural counter-cyclical cost structure through oil-linked commodities. Hence, when volumes fall, it isn’t economic to use price to get volume for volumes sake because decremental margins on volume are so much lower than price.

The pushback might be: Yeah, well, the industry has shown periods of price compression in the past, so is it irrational?

Well, I would say that - actually - that’s not neccesarily the case. In the past, price weakness has come in times of volume growth, and weak price has been used as a function of ‘growth’ (and in JM/GAF case, getting acceptance in the market), not neccesarily to maximise short/medium-term profits. It was also used to protect their share from the shrinking asphalt business. And that isn’t neccesarily irrational - it might well be the long-term sensible decision. Actually, if you look at GAF, it probably was - now they have a foothold, even though it wasn’t so profitable to get here, and now they can focus on improving the business and improving margins.

On a pure price v.s. volume debate, now that things are more stable, I’d expect that the manufacturers will be incentivised to act rationally. Of course, theory doesn’t always translate into practice. However, it’s better to have economic theory on your side and not against you, such that it is in high fixed-cost industry like fiberglass insulation, which has no hope of holding pricing when capacity utilization slips.

The other point - the cost of TPO per square foot is ~$0.85c (I called a distributor and got a quote). The total cost of a roofing project, including all ancillaries, labour, contractor profit, overheads, insluation, etc. is $10-15. So the end project is somewhat insulated from the increasing price of TPO. Also, TPO is still cheaper than PVC and asphalt by a factor of 50-100%, so there is not really substitution risk.

Below is an example BOM from a project I found online in 2017. The Genflex TPO membrane (line-2 - Genflex is Firestone) is only a fraction of the materials, even before labour.

And then lastly - distributors don’t want pricing to go down, that’s bad for business as it devalues their inventory. Contractors don’t really care that much, from the checks I’ve done. So this isn’t a super transperant industry like automotive where you go to a dealer and get a price - it’s a bit more nuanced than that in terms of its overall impact on the end customer. This, I think, aids the industry’s pricing-power.

In summary, there have been some pretty significant changes in the industry which have taken place over the past few years, which have been over-shadowed by increasing margins on large price increases. We need to see how they play out, but I think just automatically assuming that we go back to 22% pre-covid margins is probably not right. Can the industry hold 31%? Maybe not. But even if we give a few points back, Carlisle is way too cheap.

Quality of financials

It’s obviously high-margin and high ROIC. In 2022, the roofing business did ~$1.2bn in EBITDA. It did ~$135m (3.5% of sales) of capital spending (including a new TPO plant and ISO facilitiy, so an elevated year - historically it averages 2-3%). The company no-longer discloses asset base by segment, but in 2020, it had a total asset base of ~$2bn. Hence, it has an operating return on assets of likely well north of 50%. Theoretically, in normalised WC environments, FCF conversion should be ~90-95%.

There are a few attractive financial charecteristics of the business:

Variable cost-base. 85% of COGS are raw materials. You get a double-whammy effect in downturns of buying less volume and cheaper prices (generally, oil prices fall in recessions). This is how Carlisle protects its margins in downturns.

Capital light. It doesn’t need much capital to grow - that’s evidenced by the 2-3% of revenues spent on capex over time, despite MSD-HSD growth rates.

Leverage is modest at ~1.4x EV/EBITDA.

70% of the roofing business is re-roof, and that is medium-term non-discretionary. You can kick the can down the road with a patch here or there for a few years if you’re really tight on cash, but you ultimately have to replace a broken roof. A key catalyst for this is often the warranty - if a roof goes out of warranty, you don’t want to hold onto it when it gets smashed by a storm, or inevitably leaks and causes internal damage to the structure of the building. So, although sales volumes might fluctuate a bit in a down-market, you can hold onto your hat knowing that in 3-4 years sales will be fine and indeed probably a bit higher, and re-roof projects don’t go away - they simply get deferred. Such was the experience in the GFC, as volumes recovered quite well and rather more quickly than other building products (see above volumes around GFC period).

Unattractive charectieristics of the business:

Roofing has a fair bit (~30%) of exposure to new-commercial, which is cyclical. The waterproofing business, which is a smaller percentage of profits (~15% today) has ~50% exposure to residential and ~50% exposure to new-build. This is much more cyclical (and will be down this year in the double digits). Hence, the total business is cyclical. It’s just not as cyclical as people might think. But yes, rising interest rates is generally not good for the business in the short-term. Nor is tightening of lending standards. Hence why the stock is down nearly 20% in a week.

I can’t say with certainty that the industry will remain rational. I believe, through my work/checks, that it will be (obviously that’s why I own it). But there is a risk that IKO or JM get really aggresive. This isn’t a monopoly and you can’t say with certainty how pricing will play out. That’s why there is the oppourtunity, I guess.

In summary, yes - I think this is a very nice business. It generates a lot of cash, it generates a little more in good markets and in bad markets it generates a little less. It operates in a stable competetive set, and I think I can understand that pretty well. It sells a product that the world needs and is perhaps one of the least tech-disruptable products out there. Software might eat the world but it won’t keep rain from seeping into your building envelope. It has some strong non-economic drivers, meaning that I can say with, again, a reasonable degree of confidence that volumes will be higher in 5-10 years (on average) than they are today, because storms will continues to ruin roofs, and we need to replace them.

It’s not microsoft, but it’s a nice business, and I can say with much more confidence what this company will look like in 10 years than I can say about Microsoft.

Growth - Go Green or Go Home

There are two key structural drivers of growth for the company.

Growing re-roof demand

It’s pretty simple. Over time, the stock of roofs has increased, meaning that replacement demand has a tailwind behind it. The typical life of a roof is 20-30 years - some say 20-25. As you can see below, a considerable percentage of the roofing stock was constructed 2000-2012, meaning that in the 2020/25-2030/35+ period (based on 20-25 year average life of a roof), Carlisle will benefit from a tailwind of re-roofs. It’s impossible to quantify but management believes it is supportive of ~MSD growth for the roofing business.

Green Buildings

I’m not going to write a green buildings thesis here (I might do so in another post). Just go read about it. This is a good resource to start. There is significant fiscal support and private sector support (net-zero pledges) behind decarbonizing buildings. This is a decent article, ableit a bit more focussed on residential. The AIA 2030 commitment is good to read about too. Point is - if we want to get to net-zero, we need to decarbonize buildings.

There are lots of ways to take emissions out of buildings. If we think about building emissions as just those that are emitted at the building (not including the emissions in the steel, cement, etc.), the the biggest culprit is HVAC. HVAC systems are not just energy-hungry, but they also generally rely on fossil fuels. One of the easiest ways to save energy in the building is to use the HVAC system less intensely, and to do that, the building envelope needs to be more efficient. That could mean more insulation, a white roof that reflects light, a tighter air barrier to keep the cool air in, more coatings/adheisves to seal potential gaps, etc.

Over the years, Carlisle has transformed itself from a “roof membrane vendor” to a “buildings envelope company”. They’ve grown both via acquistion and organically to be the largest PolyIso insulation manufacturer in the US (the most popular type of roof insulation), and they’ve also added ancillary products such as air barriers, spray-foam insulation, water barriers and roof coatings. All of these aid in making the envelope more efficient. A few good snips below that illustrate the company’s products.

The biggest and simplest one is that the intensity of insulation is increased - i.e. instead of putting X amount of insulation per squarefoot of roofing membrane, you’re now going to put 1.2 or 1.3x. This trend has already been happening and will continue in the future. Here is an example of how PolyIso intensity has grown over the years.

Spray-Foam is also a secularly growing area due to its increased efficiency relative to traditional bats and/or plastic boards. It’s growing in both residential and commercial applications. The industry has been consolidating over the past 5 years as well. R-Value requirements in buildings are going up, driven by codes that will only intensify, and spray-foam is a great way to achieve higher R.

Beyond the product content story, there is a higher-level trend for retrofits. It’s very hard to quantify, but the push to make existing buildings more efficient could increase general activity levels. A 15-year old building with an asphalt roof might accelerate the roof replacement to a white reflective TPO membrane with 2x polyiso insulation, for example - a decision which is not driven by the current condition of the roof, neccesarily. ROIs on this stuff are uncertain and I’m cognizant that the EU’s push to retrofit existing buildings has by-and-large not been succesful (very hard to get the ROIs). At the margin, it may help, and policies/incentives/carbon prices in the future might help.

So, all of this is very hard to measure. The point is that content will grow over time for energy saving products, and it will grow at above GDP levels.

Putting together the re-roof oppourtunity + increased content from energy efficiency, it seems totally plausible that the company can achieve its ~MSD targets going forward.

Other growth drivers

There are some other smaller drivers which might add a point here or there. Those include:

Further share gains from Asphalt. Asphalt has been a share donor for the past 50 years, but has now shrunk to ~10-15% of the market. The share will slowly continue to bleed over time, but it won’t be the same tailwind that it was in the past. But the company could still take a few points of sales in the coming years.

Labour efficiency enhancing products. Labour in the roof contractor market is tight and only getting tighter as not many youngsters are coming into the industry. Carlisle has a number of time-saving products which are sold at a premium, but help the contractor net-save time/money. The biggest one is the 16-foot TPO plant. You can read about it here. It is still ramping and my recent checks suggested it hasn’t properly hit the market yet. But the company can drive some mix benefit through R&D.

EU/Global expansion of EPDM membranes. I was recently at a trade show in Sydney and was surprised to see Carlisle there. They haven’t sold a single square-foot here (going back to difficulty getting into the supply chain), but it’s a possibility. They have a position in Europe and recently expanded their Germany facility.

Metal Roofing - its is only 10% of sales but growing faster and has a much higher (~2x) ASP.

Numbers - valuation and forecasts

Share Price: $224.32

Market Cap: $11.4bn

Debt: $2.2bn

EV: $13.6bn

2023e EPS: $21.20

2023e P/E: 10.6x

2023e EBITDA: $1,559

2023e EV/EBITDA: 8.7x

Forecasts

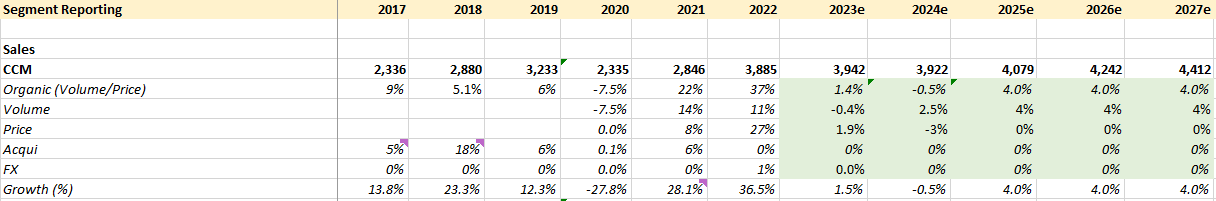

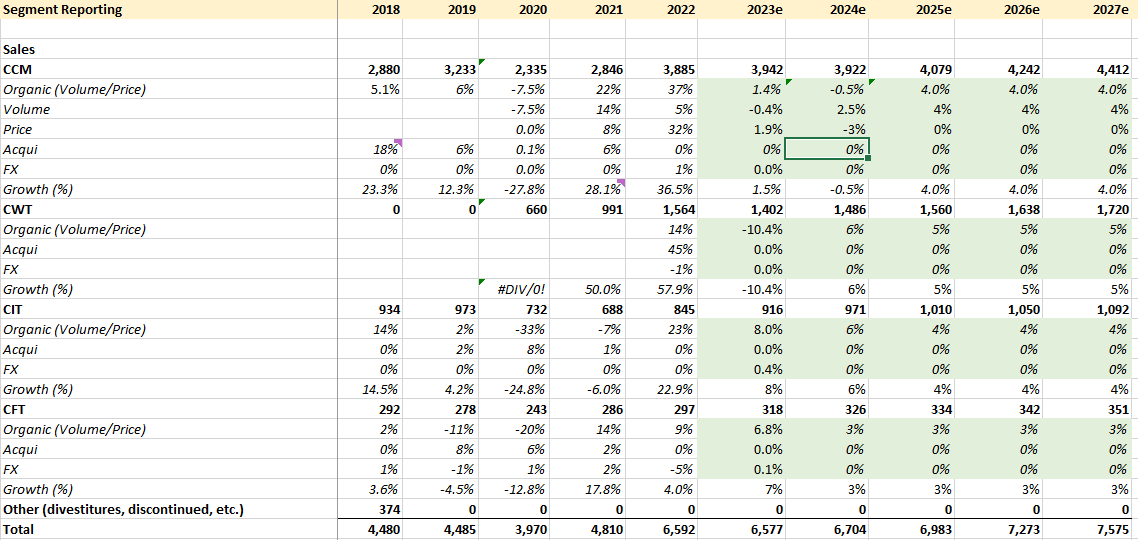

Below are my forecasts for CCM:

For CCM, I have 2023 slightly higher. It is a mixture of carry-over pricing from 2023 and some slightly negative volumes. That is mostly due to -25% volume in 1Q23e, as there is a big destock currently going on. The rest of the year is modest LSD growth, as channels suggest that backlogs are still healthy and expecting sell-through growth. Then, in 2024, I have volumes down 4%, except for the reversal of the destock in 1Q which won’t persist. So whilst it looks like I have volumes +2.5% YoY - that actually means volumes down ~4% on a normalised basis. See below.

I then have price going -3% in 2024. If we have a recession, raws will come down and I suspect that the manufacturers will have to give a bit of price back. Who on earth knows how much they’ll give back. The worst ever pricing year that this business had was 2009 when prices were down ~3.4%. I think am being overly conservative here - I don’t actually think prices will fall that much, but want to illustrate that even with conservative assumptions the case still stacks up.

I then have pricing flat on goes forward basis, and volumes returning to a ~4% CAGR (right at that MSD guide, and not giving any benefit from bounce-back in demand post-2024). I think my volume forecasts are pretty conservative, unless the world ends.

Also, it’s worth noting that whilst volumes have been robust in recent years, they have only grown at ~4.1% CAGR from 2019-2023. And on my assumptions, the volume growth from 2019-2027 will be ~3.8%. So I think that is fair.

Then, on margins, I have price dropping through at -100% incremental in 2024e and volumes at a 0% incremental. This resets margins to 28.3% (down from 31.6% at peak), and they gradually grow a little bit from there in the future at ~10pts/year. In 2020, the biz did ~26% margins.

One quick thing to note - margins look like they jumped a lot from 2019-2020. There are two reasons. (1) oil prices. (2) re-ratement of the waterproofing business into its own segment. I estimate that on a comparable basis, 2019 EBITDA margin was probably ~23% and 2018 ~20%.

I’d also note that the business has improved its cost base over this time as well - its isn’t just price - it has opened new, more efficient plants, and acquired businesses which have raw material synergies. So my assumptions are for ~5 points of structural margin improvement out of the ~8.5 points that we’ve seen so far. In-fact, the company thinks that EBITDA margins will be up in 2023e over 2022, but I’ve modelled them slightly down just to be conservative.

Here are the assumptions for the other businesses. I don’t go into a huge amount of detail but you can email me (or leave a comment) if you want to see my model. I have modelled out CIT and CFT. I assume that they got sold at ~the same multiple as Carlisle group company, which means that it doesn’t change the multiple whether you have them in there or not. Getting rid of them is not so much about unlocking value as it is about simplifying the story for investors. There is some upside I think to the multiples but it isn’t a huge needle mover.

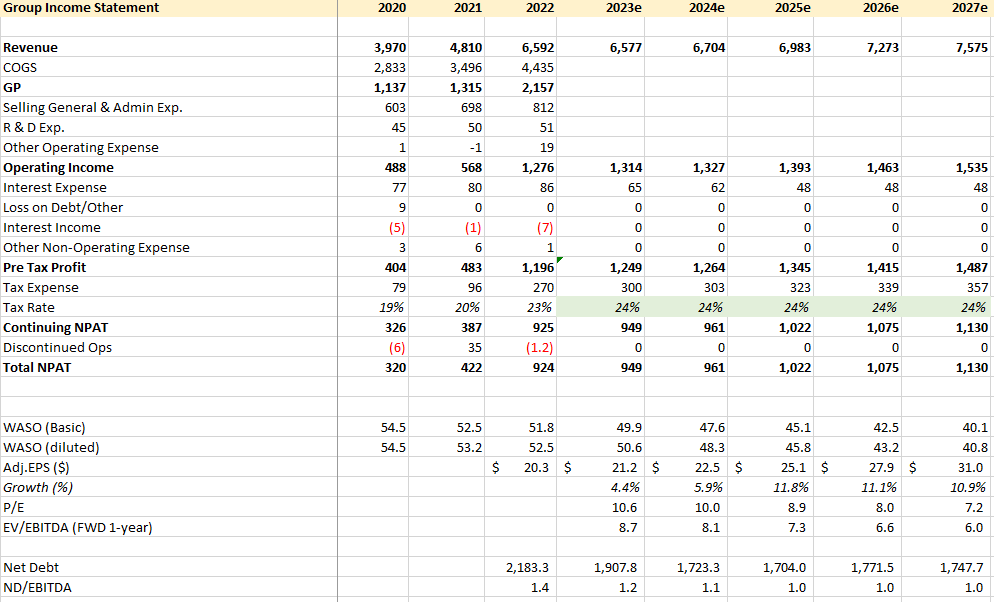

And then here is group earnings.

The last assumption is buybacks. I keep ND/EBITDA constant at 1.2x and funnel everything into buybacks. I grow the share-price at 15% P.A. Obviously if the shares increase by more than that, it will impact terminal EPS. But if the shares go up by 15% P.A. I’ll still be happy.

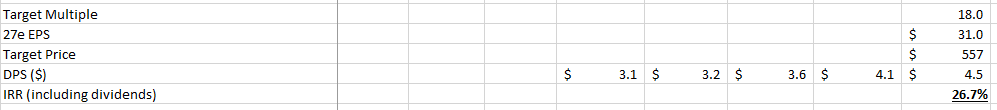

I use 16x P/E on $28.9 of EPS in 2027 to get the target price of $462. There are some small dividends of ~$3.5-4/share. That gives you an IRR of ~21% by capitalising it at Dec-26 with 16x NTM 2027e EPS. There’s upside to this if you think margins can hold the line a little higher.

Let’s get bearish, baby!

Okay - lets get bearish margins and say we go back to 22%. What does that look like? Keeping everything else the same, this is how our EPS and valuation comes out:

I’ve also gotten brought the target multiple down to 14x P/E.

Well, we still get a respectable 11% IRR.

Let’s get bullish, baby!

Now lets see what we get if we hold margins at 31% and the market gives us the nice ESG 18x P/E multiple.

That gets us a nearly 27% IRR.

So - base case = 20% IRR, bullish = 27% IRR, and if I’m wrong on margins and multiple, we still make 11% IRR. The disruption risk in the roofing business is nearly nil, and the ability for companies to oversupply it is also low, given that we have visibility over volumes for 3-5 years, unless we have another GFC (but we can just pull down lines and right-size the biz, like they did in the actual GFC).

That’s a nice risk/reward for the long-term investor.

Summary

I think Carlisle is a very nice business which is not appreciated quite as such. There are still question marks around where margins shake-out, but I think the risk/reward is very attractive for this highly cash-generative business with structural tailwinds.

Hence, I am long.